Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Indigenous Health

Indigenous Health

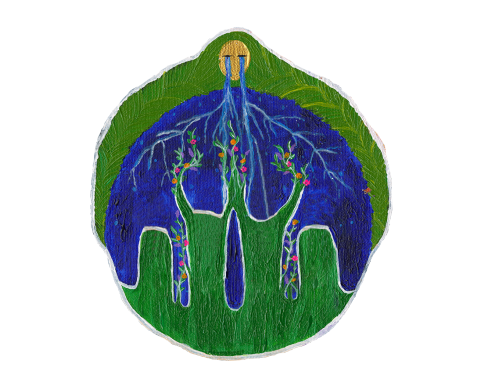

To understand and practice Indigenous health, there must be respect for Indigenous Peoples, their world views, ways of knowing, and cultural practices.

The concept of health for Indigenous Peoples is relational. In other words, the state of being in good health requires alignment of physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and environmental health. The medicine wheel, which contains four balanced sections, illustrates how complete health and wellbeing can be achieved.

Relationship-based care is an intentional caring relationship between health care professionals and the people they serve. This relationship is foundational to a healing environment.

To understand and practice Indigenous health, there must be respect for Indigenous Peoples, their world views, ways of knowing, and cultural practices.

The concept of health for Indigenous Peoples is relational. In other words, the state of being in good health requires alignment of physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and environmental health. The medicine wheel, which contains four balanced sections, illustrates how complete health and wellbeing can be achieved.

To understand and practice Indigenous health, there must be respect for Indigenous Peoples, their world views, ways of knowing, and cultural practices.

The concept of health for Indigenous Peoples is relational. In other words, the state of being in good health requires alignment of physical, mental, emotional, spiritual, and environmental health. The medicine wheel, which contains four balanced sections, illustrates how complete health and wellbeing can be achieved.

Relationship-based care is an intentional caring relationship between health care professionals and the people they serve. This relationship is foundational to a healing environment.

Relationship-based care is an intentional caring relationship between health care professionals and the people they serve. This relationship is foundational to a healing environment.

For arthritis health care providers – Providing culturally safe and humble care

For arthritis health care providers – Providing culturally safe and humble care

Cultural safety is an outcome based on respectful engagement that recognizes and strives to address power imbalances inherent in the healthcare system. It results in an environment free of racism and discrimination, where people feel safe when receiving health care.

Cultural humility is a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust. Cultural humility involves humbly acknowledging oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience.1

We kindly invite you to learn more by visiting First Nations Health Authority’s #itstartswithme Creating a Climate for Change.

Creating a culturally safe and humble healthcare system first requires commitment to self-reflection and relearning colonial ways at an individual level. While self-depreciation is not encouraged, those that engage in decolonizing processes may find that they carry a sense of shame, discomfort, and even a physical heaviness. Remember, that is all a part of the journey to become a better ally and a more conscious human being.

Health care providers must engage in co-learning initiatives that will lead to an improved and clearer understanding of what wellness means from an Indigenous perspective and recognize the socioeconomic factors such as income and education that influence a person’s physical, mental, emotional, and social health. Practicing cultural humility is about “being open to learning and comfortably starting with what we don’t know.” It is the foundation of building a trusting relationship where power is shared between health care professionals and patients and decisions are made in partnership.

Only spaces that are nurturing and conducive to growth are deemed culturally safe. First, this requires an evaluation of barriers to accessing the health care services, including competing priorities and transportation. Offering patients, a choice of in-person and remote options, or a bus service may help to support engagement. Secondly, gaining acceptance from all members of the team including administrative staff and medical technicians. It is important that everyone understands care starts from the first interaction, whether that is over the phone or in person. Lastly, creating welcoming environments requires thoughtful consideration in terms of design, including décor, pictures, and seating.2

We kindly invite you to learn more by visiting Canadian Nurses Association’s Indigenous Health website here.

References

References

- First Nations Health Authority (2022): #itstartswithme Creating a Climate for Change (https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Creating-a-Climate-For-Change-Cultural-Humility-Resource-Booklet.pdf)

- Canadian Nurses Association: Indigenous Health (https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/policy-advocacy/advocacy-priorities/indigenous-health)

For patients and caregivers – Speaking up

For patients and caregivers – Speaking up

No matter your ethnicity, you have likely experienced unfair treatment due to inherent characteristics that you cannot change. This includes your age, sex, gender, health literacy and so forth. You may have also witnessed others being treated unfairly for no “apparent” reason in a doctor’s office, at the pharmacy or in a hospital setting.

While research shows that discrimination occurs more widely in certain groups of people compared with others and everyone plays a role in that. A passive spectator of a crime is accountable to upholding justice and reporting the event to authorities. The same can be said about racism in the healthcare system – a passive spectator who does not act, only reinforces existing structural inequities.

Learn more about how to advocate and be a good ally to Indigenous Peoples:

For decision makers

For decision makers

To make a tangible difference and improve the health and wellness of Indigenous Peoples in Canada, provincial, territorial, and federal governments will need to work together to address the social determinants of health, including poverty, employment, education, social support networks, housing, physical environments, and early childhood development.

Further, the solutions must be community-driven and acknowledge the diversity of Indigenous Peoples to meaningfully engage in and address patient needs, preferences, and values.

We kindly invite you to learn more by visiting the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health website here.

Resources

Resources

- Cultural Sensitivity: A pocket guide for health care professionals (Second Edition)

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control: Culturally Safe Care (Online courses and training)

- Canadian Institute for Health Information: Measuring Cultural Safety in Health Systems

- First Nations Health Authority: Cultural Safety and Humility

References

- Dumont, J. (1989). Culture, behaviour, & identity of the Native person. NATI-2105: Culture, behaviour, & identity of the Native person.

Arthritis in the Indigenous community

Arthritis in the Indigenous community

The data presented below come from non-Indigenous led research.

Arthritis affects Indigenous Peoples more significantly and more severely than in non-Indigenous populations. Specifically, Indigenous Peoples in Canada experience:

- Higher rates of inflammatory arthritis such as lupus, rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis (Hurd & Barnabe, 2017).

- Higher rates of death from lupus and its complications compared to non-Indigenous patients (Hurd & Barnabe, 2017).

- Worse disease outcomes in early rheumatoid arthritis compared to white patients. This means slower improvements in pain and swelling and less likelihood of achieving remission (i.e., getting the disease under control) (Nagaraj et al., 2018).

- Experience fewer visits to specialists than the non-Indigenous population as well as significantly more hospitalizations due to arthritis complications (Loyola-Sanchez et al., 2017).

- Have lower rates of evidence-based inflammatory arthritis therapies being used among Indigenous people despite the disease being more severe (Thurston et al., 2014).

Arthritis is also the leading cause of disability amongst Indigenous Peoples across Canada. Further, it can compromise the ability of individuals to participate in traditional activities, such as harvesting country foods, and traditional crafts.

(Ng et al., 2011)

Why is this the case? The answer is multidimensional. Intertwined pathways of genetics, environmental factors, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors all play a role in the development and progression of chronic conditions such as arthritis. Interestingly, the same study by Barnabe and colleagues found that Indigenous Peoples were more likely to visit a doctor than non-Indigenous, but less likely to have specialist visits (Barnabe et al., 2017). This speaks to gaps in the continuity of care that have been left unaddressed, especially for those who live in remote or rural areas (Ng et al., 2011). While there is some evidence to suggest that health care utilization is higher in Indigenous communities. This is the downstream effect of the insufficient investment in public health initiatives that target primary prevention and self-care. This leaves many without guidance and support until the end stages of their disease, which costs more to treat. Inclusive models of care that provide education and continuous support are needed.

One way of structurally enhancing the quality of care for Indigenous Peoples is through patient engagement in research that aims to generate real world solutions by patients for patients. Although research with Indigenous communities is moving toward equitable partnerships that are built upon mutual understanding, trust and transparency, community engagement with Indigenous communities has been lagging. A review by Lin and colleagues examined the level of community engagement reported in arthritis studies conducted in Australia, New Zealand, the United States and Canada. They found that only 34% (n = 69) of the 205 studies identified reported community engagement at any stage of research. While only 4 studies described meaningful community engagement through all stages of the research (Lin et al., 2018). Avoiding performative engagement, otherwise known as tokenism, is the highest priority. It is time to call on stakeholders to make an investment in relationship building and engaging Indigenous Peoples in research.

More recently, a group of researchers from Arthritis Research Canada highlights local Indigenous knowledge and expertise through the “arthritis liaison” initiative. The protocol was co-designed with the community to support culturally relevant patient-centred care plans. The arthritis liaisons were community members with local expertise and connections that served as a bridge between health care providers and patients. The study allowed patients to receive coordinated care within the community while building local capacity (Umaefulam et al., 2021). Acknowledging the diversity of Indigenous Nations, similar models should be pilot tested across all provinces and territories.

References

References

- Barnabe, C., Jones, C. A., Bernatsky, S., Peschken, C. A., Voaklander, D., Homik, J., Crowshoe, L. F., Esdaile, J. M., El-Gabalawy, H., & Hemmelgarn, B. (2017). Inflammatory Arthritis Prevalence and Health Services Use in the First Nations and Non–First Nations Populations of Alberta, Canada. Arthritis Care & Research, 69(4), 467–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/ACR.22959

- Hurd, K., & Barnabe, C. (2017). Systematic review of rheumatic disease phenotypes and outcomes in the Indigenous populations of Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand. Rheumatology International, 37(4), 503–521.

- Lin, C. Y., Loyola-Sanchez, A., Hurd, K., Ferucci, E. D., Crane, L., Healy, B., & Barnabe, C. (2018). Characterization of indigenous community engagement in arthritis studies conducted in Canada, United States of America, Australia and New Zealand. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.11.009

- Loyola-Sanchez, A., Hurd, K., & Barnabe, C. (2017). Healthcare utilization for arthritis by indigenous populations of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: A systematic review☆. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46(5), 665–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SEMARTHRIT.2016.10.011

- Nagaraj, S., Barnabe, C., Schieir, O., Pope, J., Bartlett, S. J., Boire, G., Keystone, E., Tin, D., Haraoui, B., Thorne, J. C., Bykerk, V. P., & Hitchon, C. (2018). Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Presentation, Treatment, and Outcomes in Aboriginal Patients in Canada: A Canadian Early Arthritis Cohort Study Analysis. Arthritis Care and Research, 70(8), 1245–1250. https://doi.org/10.1002/ACR.23470

- Ng, C., Chatwood, S., & Young, T. K. (2011). Arthritis in the Canadian aboriginal population: North-south differences in prevalence and correlates. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(1).

- Thurston, W. E., Coupal, S., Jones, C. A., Crowshoe, L. F. J., Marshall, D. A., Homik, J., & Barnabe, C. (2014). Discordant indigenous and provider frames explain challenges in improving access to arthritis care: A qualitative study using constructivist grounded theory. International Journal for Equity in Health, 13(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-13-46

- Umaefulam, V., Loyola-Sanchez, A., Chief, V. B., Rame, A., Crane, L., Kleissen, T., Crowshoe, L., White, T., Lacaille, D., & Barnabe, C. (2021). At-a-glance - Arthritis liaison: a First Nations community-based patient care facilitator. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice, 41(6), 194. https://doi.org/10.24095/HPCDP.41.6.04