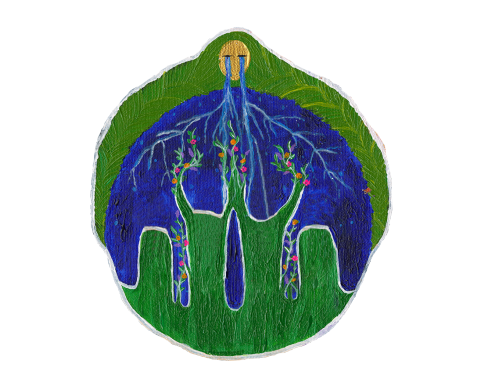

Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Kaamotaan (Reconciliation) –

Cleansing as Healing

Courtney Alexandra Fox

Colonization

Colonization

Colonization is the act of exerting control over a geographical area, including its peoples. It occurs when one nation conquers another while exploiting natural resources and dismantling language and culture.

In the health care context, the path to culturally appropriate and timely care for Indigenous Peoples living with inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis is shadowed by systemic racism, implicit bias, and geographical challenge.

Arthritis researchers, health care professionals, patient organizations and their members, and the pharmaceutical industry must start at the beginning to fully understand the intergenerational trauma and deep pain Indigenous Peoples with arthritis continue to deal with because of policies such as the Indian Act (1876) and Indian Residential and Day Schools.

Colonization is the act of exerting control over a geographical area, including its peoples. It occurs when one nation conquers another while exploiting natural resources and dismantling language and culture.

In the health care context, the path to culturally appropriate and timely care for Indigenous Peoples living with inflammatory and non-inflammatory arthritis is shadowed by systemic racism, implicit bias, and geographical challenge.

Arthritis researchers, health care professionals, patient organizations and their members, and the pharmaceutical industry must start at the beginning to fully understand the intergenerational trauma and deep pain Indigenous Peoples with arthritis continue to deal with because of policies such as the Indian Act (1876) and Indian Residential and Day Schools.

The colonization legacy in Canada

Arthritis affects Indigenous Peoples more significantly and more severely than in non-Indigenous populations. The legacy of more than 140 years of colonization – the disregard for core values and failure to provide culturally relevant care – has created health inequities that have resulted in higher occurrence and worse outcomes.

To understand colonization in Canada is to acknowledge how a settler mentality and the Canadian government systematically blocked the deep connection between Indigenous Peoples and their ancestral land, culture, and community through the implementation of policies designed to assimilate and deprive Indigenous Peoples the rights they were promised.

The Indian Act in 1876, which is still in place today, formally set into motion a process designed to erase the distinct legal, social, and cultural identities of Indigenous Peoples. The Truth and Reconciliation (TRC) report, published in 2015, made it clear that the measures under the Indian Act were part of an effort to assimilate Indigenous Peoples against their will, characterizing this practice as "cultural genocide."1

According to the TRC report, the aim of the Indian Act was to “absorb” Indigenous Peoples into mainstream Canadian life. Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott outlined this policy in 1920, when he told a parliamentary committee that “our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.”2

The colonaization legacy in Canada

These goals were reiterated in 1969 in the federal government’s Statement on Indian Policy (more often referred to as the “White Paper”), which sought to end Indian status protection for Indigenous Peoples and terminate generations-old Treaty rights the federal government had negotiated with First Nations.

These goals were reiterated in 1969 in the federal government’s Statement on Indian Policy (more often referred to as the “White Paper”), which sought to end Indian status protection for Indigenous Peoples and terminate generations-old Treaty rights the federal government had negotiated with First Nations.

Under the Indian Act, Canada asserted control over Indigenous Peoples’ lands. In some cases, Canada negotiated land treaties with Indigenous Peoples; in others, the Government simply occupied or seized Indigenous land. The negotiation of treaties, while carried out legally, was often marked by fraud and coercion.

- For coercion, see: Ray, Illustrated History, 151–152.

- For fraud, see: Upton, “Origins of Canadian Indian Policy,” 56.

- For failure to implement Treaties, see: Sprague, Canada’s Treaties with Aboriginal People, 13. For taking land without Treaty, see Fisher, Contact and Conflict.

In the 1880s, Canada, without legal authority, enforced an “Indian Pass System” that unlawfully confined Indigenous Peoples to their reserves and stripped them of power. Later, the Canadian government forced Indigenous Peoples to relocate their reserves from agriculturally valuable or resource-rich land to more remote regions with limited economic potential.

For examples from Saskatchewan, see the following books:

- Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, Fourth Edition by J.R. Miller

- The Knowledge Seeker: Embracing Indigenous Spirituality by Blair A. Stonechild

- Big Bear by Rudy Wiebe, John Ralston Saul (Editor)

During this period, Government policies and laws outlawed traditional spiritual practices and resulted in the imprisonment of spiritual leaders and confiscation of sacred objects from communities.

- For an example, see: An Act further to amend “The Indian Act, 1880,” Statutes of Canada 1884, chapter 27, section 3, reproduced in Venne, Indian Acts, 93.

In 1883, Canada's first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald declared that the government also intended to separate Indigenous children from their families and send them to residential schools - not as a measure of education but solely with the intent of breaking the link to their culture and identity. Speaking to Parliament, Macdonald said:

“When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”

Canada, House of Commons Debates (9 May 1883), 1107–1108.

In establishing residential schools, the Canadian government essentially judged Indigenous Peoples to be unfit parents and that parenting was better left to institutions to “civilize and Christianize” Indigenous children, while enforcing strict regulations against speaking native languages and honoring cultural traditions. The tragic consequences included siblings being separated from each other and families struggling with intergenerational trauma, as well as lost language and identity.

The residential school experience of First Nations, Inuit and Métis children in Canada endured for generations until the last one finally closed its doors in 1996. Despite the collective measures to eliminate Indigenous Peoples culture in favour of assimilation into Euro-Canadian society over the past 150 years, they have failed to achieve these policy goals. Although Indigenous Peoples and cultures have been severely damaged, they continue to exist. Indigenous Peoples have refused to surrender their identity. It was the former students, the Survivors of Canada’s residential schools, who placed the residential school issue on the public agenda. Their efforts led to the negotiation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in 2008 as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement. Its mandate was to document the history and lasting impacts of the residential school system on Indigenous students and their families. Over a seven-year period, the TRC provided residential school survivors an opportunity to share their experiences during public and private meetings held across the country. In 2015, the TRC released an executive summary of its findings along with 94 Calls to Action regarding reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous Peoples.

According to the Truth and Reconciliation report, Residential Schools had impacts on the physical, social, and emotional health of children who attended them, and on the generations that followed, including:

- medical conditions

- mental health

- post-traumatic stress

- changes to spiritual practices

- loss of languages and traditional knowledge

- violence

- suicide

- effects on gender roles, childrearing, and family relationships

The long-term effects of residential schools are still being felt in Canada today, reaching far beyond those forced to attend these schools. Survivors and their families live with a legacy that includes powerlessness, low self-esteem, as well abuses inflicted by teachers on students, which were tragically normalized within the system itself.

How do you respond to the legacy of colonization and start the journey towards Truth and Reconciliation?

How do you respond to the legacy of colonization and start the journey towards Truth and Reconciliation?

Acknowledging and reconciling our past and present and future are fundamentally important to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous Peoples and all Canadians. Our hope is that the arthritis leaders, like others, continueto self-reflect and take action to lead and support positive change among non-Indigenous arthritis patients, clinicians, and researchers.

“Where do I start?” is often the first question one asks oneself after a learning session on Indian residential schools and the Indian Act. The legacy of Colonialism and racism leaves one wondering how to integrate Truth and Reconciliation practices into one’s life, at work and in our communities. As the starting point for this work, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation encourages settlers-colonials to ask and answer the following questions, and act where you know there is a lack of knowledge or understanding about the events of the last 140 years. The work begins within.

- Do I know any Indigenous people? If not, why?

- Have I ever participated in ceremony? If not, why?

- Am I able to name the traditional territory I stand on? If not, why?

- Have I meaningfully engaged in deep conversation with Indigenous people? If not, why?

- Have I read an Indigenous author? If not, why?

Answering these questions is essential to walking on the reconciliatory path at the individual, organizational and health system level.3

Resources

Below is a list of links that provide additional information to help you and your organization on the Truth and Reconciliation journey. This list is a suggested starting point:

- Dr. Terri-Lynn Fox, Indian Residential Schools: Perspectives of Blackfoot Confederacy People

- National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, Truth and Reconciliation Report Calls to Action

- “The Unforgotten” – short film on the health across 5 stages of life of Indigenous Peoples, Indigenous approaches to health and racism in the health care system

- Bob Joseph, 21 Things You May Not Know About the Indian Act

- Aboriginal Health in Canada: Historical, Cultural, and Epidemiological Perspectives

- Eduardo Duran, Healing the Soul Wound

- Harvey Eagle, Connecting Cultural Safety and Addressing Racism in the h System (webinar and slides)

- The Gord Downie and Chenie Wenjack Fund - Resources

Resources

References

References

- “Introduction”, Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, page 1

- Library and Archives Canada, RG10, volume 6810, file 470-2-3, volume 7, Evidence of D. C. Scott to the Special Committee of the House of Commons Investigating the Indian Act amendments of 1920.

- CBC Radio: Wondering how to get involved in reconciliation? Start by asking yourself these 5 questions (https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/how-are-you-putting-reconciliation-into-action-1.4362219/wondering-how-to-get-involved-in-reconciliation-start-by-asking-yourself-these-5-questions-1.4364516)